My grandfather, Iwan Dudycz, died yesterday evening.

Like my grandmother, Parania, he was surrounded by his children, who kept a vigil around his bed ever since he slipped into a coma Friday morning. He was ready to join my Baba, who died on July 31st of this year. He was 93 years old and weary without her.

When I heard that he slipped into a coma, I went to see him. I knew I couldn’t speak with my Dido, that he was not conscious, but I wanted to be close to him one more time, to say goodbye. Sometimes you don’t need words.

We have different bonds with different people in our lives, different ways we show our love. With some people, it’s words; with others it’s actions or shared experiences; and with some, we show our love with affection.

Dido fell into this last category. Even before he lost his hearing, Dido was more quiet than my Baba. She was the talker, sharing stories, offering advice. Dido certainly held his own, but he was also content to let Baba ramble on and on while he sat nearby, ready to clarify or contribute something to her story.

As a grandfather, Dido was affectionate and supportive. He would often use Ukrainian terms of affection when referring to my sister and I and our cousins. He would call us his “keetsya” or “zozulka” (the Ukrainian words for kittens, cuckoo, or other cute animals). He would engulf us in a large bear hug. It’s the way we hug in the Dudycz family: big and with our whole hearts. Anyone who knows me has felt the legacy of those hugs.

The older Dido got, the more quiet and watchful he became. Where he once played the harmonica and bantered with friends, he began to spend more and more time sitting on the front stoop watching the world go by or sitting in his recliner in the living room.

I’m sure that some of it was age and the loss of his hearing, and I imagine that some of it was seeing the world change around him: friends died, neighbors moved away. His grandchildren had children and we saw each other less often as we moved into our own lives. But whenever we came together, he was happy to be with his family, proud of his children and grandchildren. His smile still had the same warmth, his blue eyes the same twinkle. His hugs may not have been as strong, but they conveyed the same big-hearted love.

I believe in my heart that he knew his children were there at his deathbed, that he felt the way they cared for him, massaged his arms and legs, kept a cool towel on his forehead, kissed him, held his hands, told him they loved him and shared memories. I believe that Dido knew when loved ones came, and he felt the prayers of family from afar.

When I saw him, I kissed the top of his head, hot from fever, in the same way I would always kiss him hello and goodbye. I knew that the next time I’d kiss him would be at the funeral home, and his body would be cold. Even if his spirit lingers for 40 days as per Ukrainian tradition, it would not be tied to that body. This was the last time he would be there in a physical way.

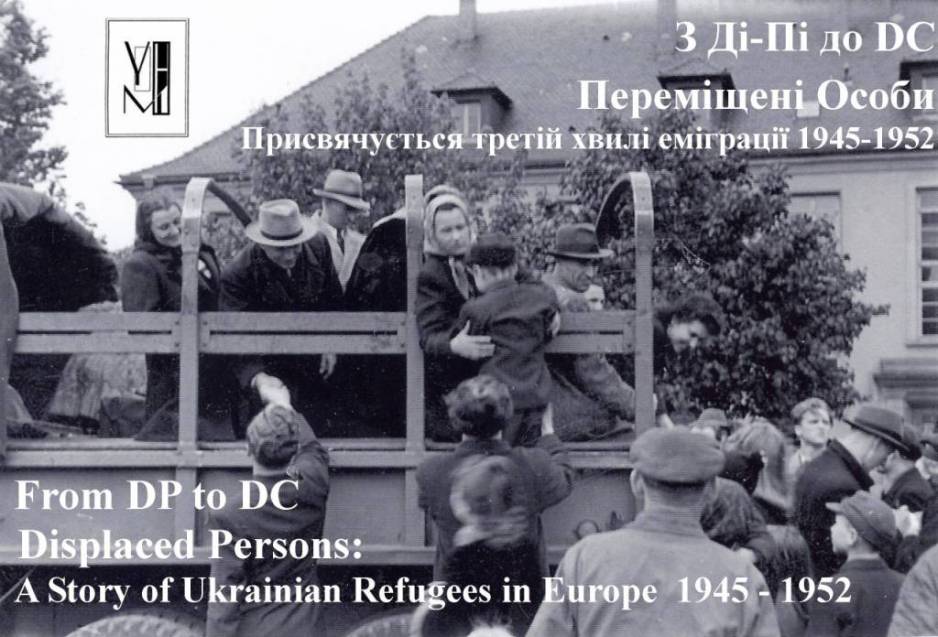

I sat beside him and held his hand, looked at the age spots on his skin, the wrinkles on his face, the soft gray hairs. Dido was a strong man and there were stories in those hands—heartache in his childhood, a youth of toil and sacrifice, war, displaced persons camps, hard labor and time spent in factories, but also so much love: meeting my Baba, raising a family, creating a home, tending his garden, holding grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His hand was warm and solid, like Dido.

Ever since I could remember, my Dido would tell me that I had his nose; the Dudycz nose. It’s true. That round ball on the tip of my nose is from his genes. It connects me to him, to my father, to my roots. When I said goodbye to Dido, I touched my nose to his, Eskimo-kiss style. My Dudycz-nose to his.

It’s still amazing to me that Baba and Dido both passed surrounded by all of their children. I am blessed to have been born into the family that they created, and I see them in my father and aunts and uncles. I even catch glimpses in my cousins and our children.

Baba and Dido will live on in us, and I look forward to the times when the extended Dudycz family will get together. I think it’s what Baba and Dido would want, for us to continue to be a family, to support one another, to be there for good times and hard times. They would want us to share their stories, to laugh and cry with their memories. Because that is also how they will live on in us. What is remembered, lives.

I love you, Dido and Baba. Vichnaya Pamyat.